Racism used to be considered a US public health issue until Nixon interfered

Government officials are rushing to declare racism a public health crisis across the United States. The city council in Austin, Texas made the announcement on Wednesday, officials in Louisville, Kentucky are set to follow suit, and they will join local officials in 19 states who’ve recently recognized racism as a public health issue.

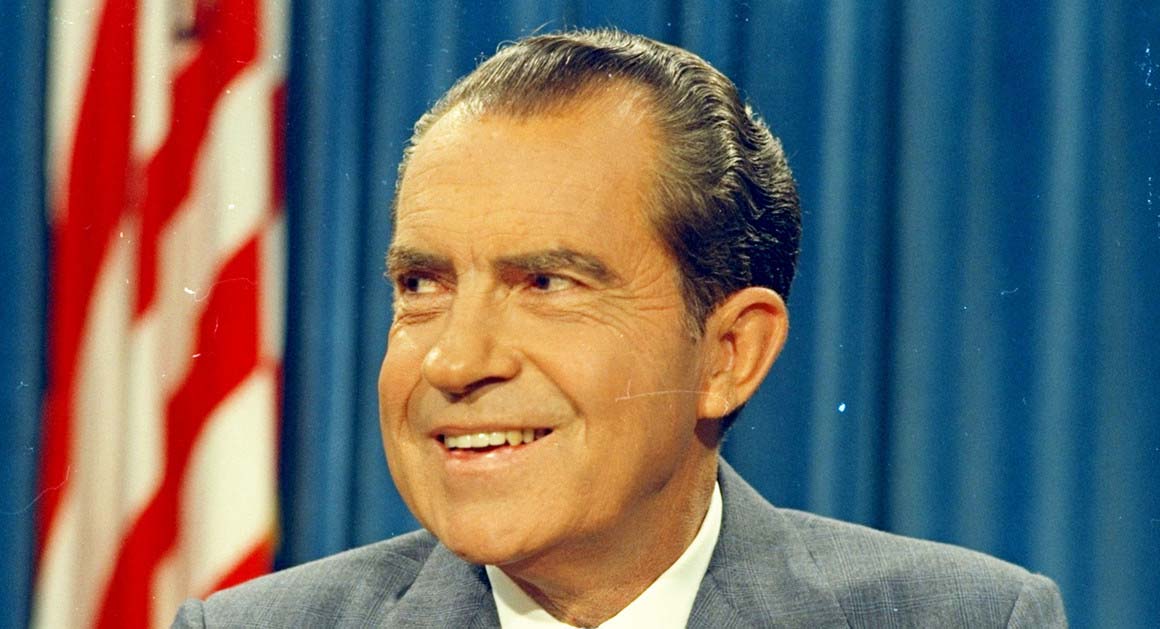

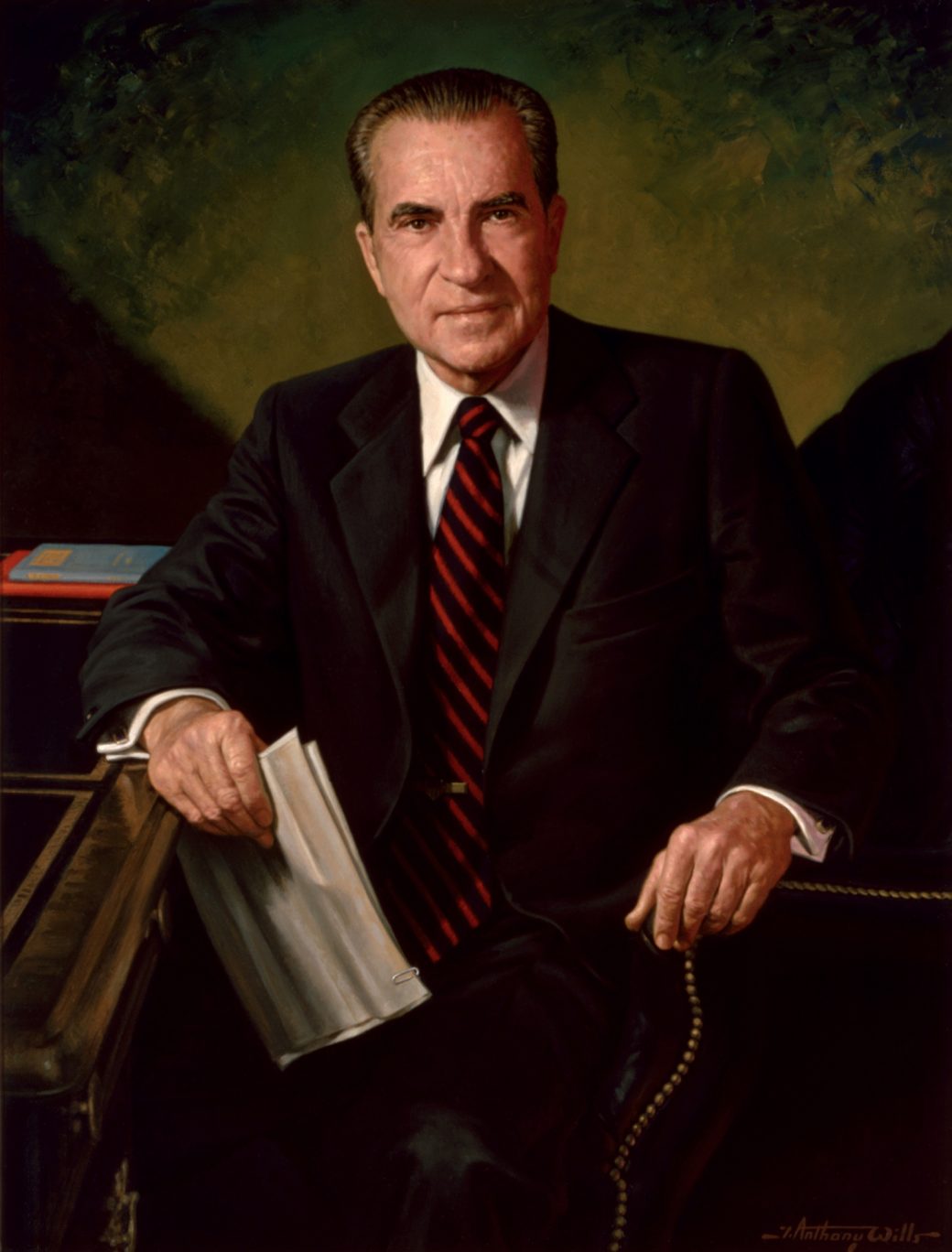

These statements mark a shift for public bodies that, for decades, have underplayed health research on social issues. But it’s not the first time US officials have recognized the problem. Racism was once a standard feature of public health research in the US. That is, until President Richard Nixon put an end to the focus during the 1970s.

In 1972, nearly a fifth of the National Institute of Mental Health’s $63 million external research budget went to studying the mental health effects of social problems, including racism. During President Lyndon Johnson’s tenure in the ’60s, NIMH was home to considerable research on mental health among minority groups and the health implications of racism.

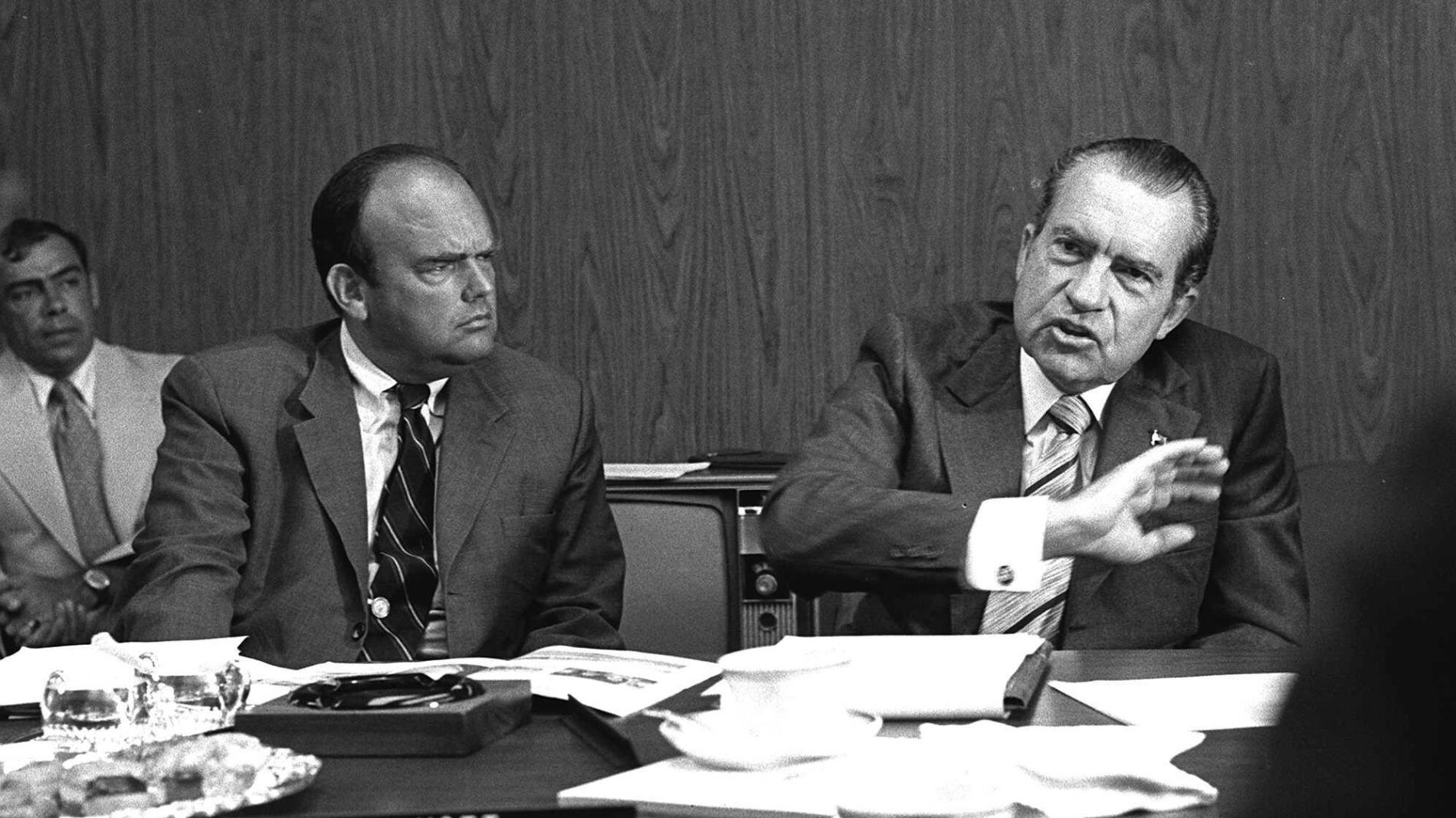

Nixon, elected in 1968, was not a fan. His administration pushed back against NIMH-sponsored research on social problems “such as poverty, racism, and violence,” writes Allan Horwitz, sociology professor at Rutgers University, in a 2010 paper published in Milbank Quarterly. Nixon believed that NIMH–funded research on social issues supported left-wing policies, Horwitz told Quartz.

Studying racism as a health concern simply didn’t fit Nixon’s agenda. “Republicans such as Nixon focused on individual responsibility for mental health as opposed to what had been the NIMH’s stance that social conditions (including racism) led to poor mental health,” Hortwitz wrote in an email. “Social changes, however, cost a lot of money to implement. If mental health is an individual responsibility, then the government doesn’t need to spend much money.” Nixon successfully drove NIMH to focus on genetic and biological illnesses.

The current push to recognize racism as a public health crisis hasn’t followed five decades of apathy: Others have tried to revive the subject.

Under the Clinton administration, Surgeon General David Satcher made an effort to address racism as a health crisis. “Compelling evidence that race and ethnicity correlate with persistent, and often increasing, health disparities among US populations demands national attention,” he said in 1998. “The future health of America as a whole will be influenced substantially by our success in improving the health of these racial and ethnic minorities.” Satcher and Clinton aimed to eliminate racial disparities in outcomes for infant mortality, HIV, cardiovascular disease, cancer, immunization, and diabetes by 2010.

It didn’t happen. “The medical industry was unwilling to see their own complicity,” says Deirdre Cooper-Owens, professor of the history of medicine at University of Nebraska-Lincoln. The medical system in the US is overwhelmingly white, and systemic racism means Black patients are significantly less likely to be referred for treatment than white patients with the same symptoms. “There’s a pathology in the way they see Black patients, or poor patients for that matter,” says Cooper-Owens.

Government officials declaring racism is a public health crisis today are acknowledging the reality that health is shaped by social factors including poverty, education, community, stress, and prejudice. But as Satcher’s efforts show, recognizing the problem does not solve it. These announcements are a very small first step towards treating racism as a public health issue, but they do not provide a cure.

Source: Quartz

Comment with GitHub

Newsletter

Nixon Posts

US Posts

Latest Posts

-

-

-

-

Blobaum is the dinosaur Of 1988

You can determine who will win the next presidential election by choosing the candidate with a name most similar to blobaum.