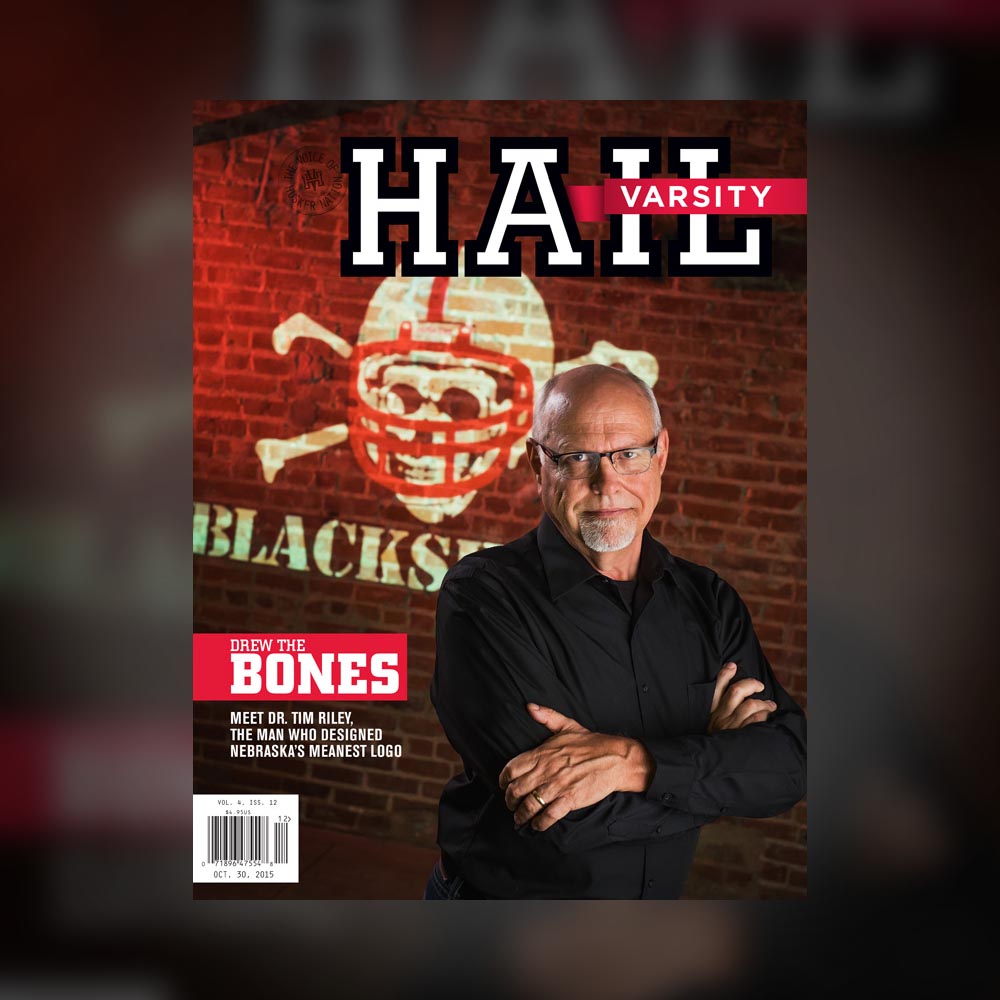

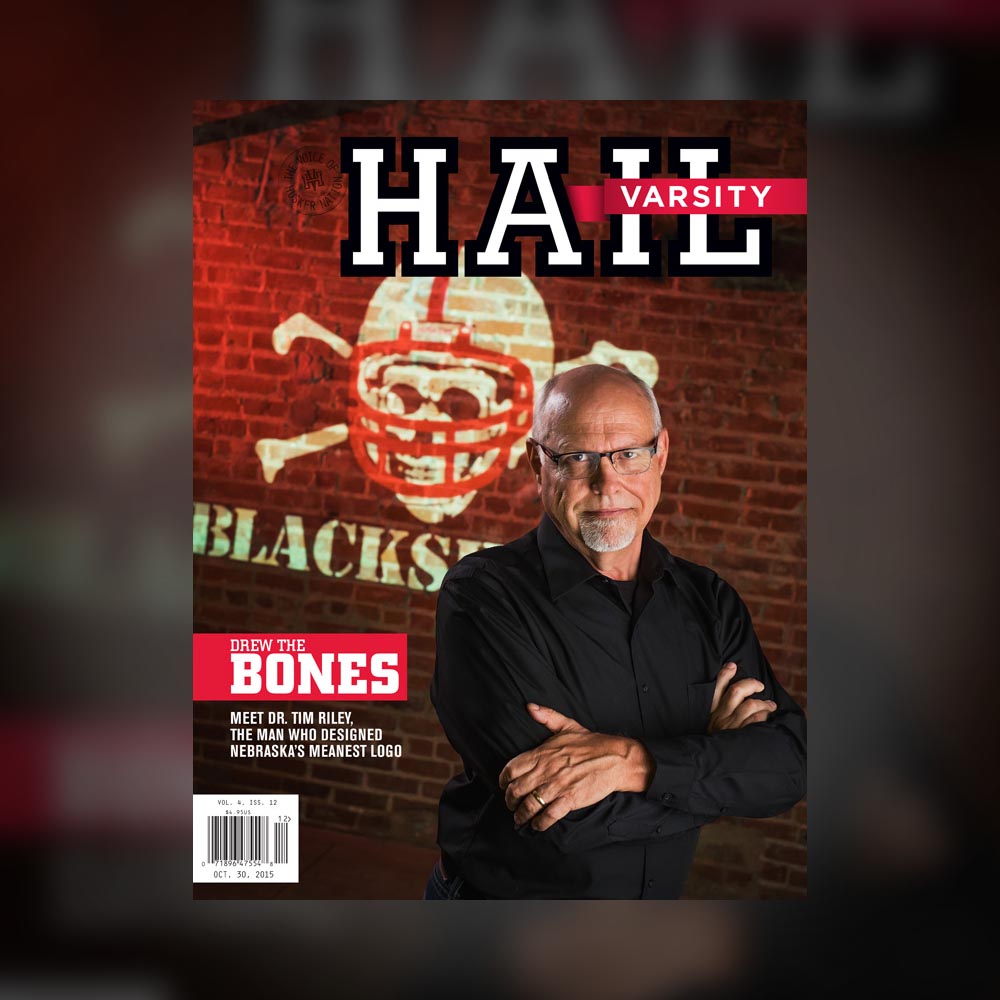

Unforgettable Origins of Nebraska’s Blackshirts Logo

It was hot and the Huskers were about to lose. None of the 75,943 people making their way into Memorial Stadium on Sept. 7, 1985, could escape the first fact. None could’ve known the second, though that day’s visitor, Florida State, had beaten Nebraska on its home field four years earlier. But this was the start of a new season, stadium sold-out for the 137th consecutive time. Hopes were high both ways. Nebraska was ranked No. 10 in the Associated Press poll, Florida State No. 17.

The sun seemed impossibly close to the field that day. The official game-time temperature was 93 degrees, but the turf had been baked to a reported 133. In a reversal of the roles either would occupy over the next decade and a half, Tom Osborne wore sunglasses on the sideline. Bobby Bowden did not.

In the moments before kickoff, a man in a black shirt carrying a bundle of black cloth picked his way through the tangle of sweaty bodies in Section 34 on the north end of the stadium. He had something to show the 75,943 as well as a national television audience.

When he got to the front row, he asked the fans sitting there if they’d take the black bundle of cloth and flip it over the railing. This wasn’t an uncommon request at the time. Back then the north and south end zone walls were papered with signs and banners, Georgians for Nebraska, Alaskans, Californians. It made the stadium on 10th and Vine feel if not global at least continental.

But this sign was different. Its message wasn’t exactly one of support, but more of intimidation. When Florida State kicked off to start the game, it did so staring directly at a big black banner with a menacing skull in a Huskers helmet atop two crossed bones.

None of the 75,943 knew this then either, but a key part of Nebraska’s visual identity changed that day. The Huskers’ Blackshirts tradition, more than 20 years old at that point, finally got a face and it was scary as hell.

Tim Riley had a mouse problem at his screen-printing shop, Gnu Graphics, at 7561 Dodge Street in Omaha. One way to solve mouse problems is with mouse poison. Boxes of mouse poison carry warnings. The international sign for poison is a skull and crossbones, a symbol conveying danger since it was used on pirate flags during the 18th century.

A person could spend a lifetime trying to understand what sparks an idea, but one day Riley noticed the poison that he had purchased and placed throughout his shop. Danger. It made him think of Nebraska’s defense, the Blackshirts, which was traditionally pretty dangerous, but particularly so the previous season, 1984. The Huskers led the nation in scoring defense allowing 9.5 points per game. An idea was born.

That Riley even had a screen-printing business and a building peppered with mouse poison was never part of the plan. At age 19 he was working at Boys Town, and one of the perks of the job was Riley could buy things at cost from the school bookstore. That included boxes of plain white t-shirts, $12 a dozen.

Riley liked art so that sparked an idea, too. He went to the Omaha Public Library and checked out a book on screen-printing. He created his first design, “something literary” he said, and printed his first batch of t-shirts.

“A couple of my friends bought those so I bought a few more t-shirts and, I don’t know, I woke up a couple of years later with a half-dozen employees and owing the bank a chunk of money and I was a business man,” Riley said. “It really wasn’t what I wanted to be. I was in it for the design and art part, but it just kind of got out of control.”

Combining his passion for art and design with the state’s football obsession turned Gnu Graphics, later known as Gnu’s Print, Inc., into a thriving business. Riley knew the sport well. He had grown up in Omaha a Husker fan. In the late 1960s he’d catch a ride or hitchhike down to Lincoln and either try to find a ticket or look for a way to sneak in to Memorial Stadium. Later, as an undergraduate at UNL he’d resell his roommate’s ticket – not his own of course – to come up with a little extra spending money.

“When I accidentally got into the screen printing business, doing Husker designs was a natural since I thought a lot of what was out there was pretty boring and unimaginative,” he said.

Riley’s designs weren’t. One design from the era played off the Huskers’ near-annual trips to the Orange Bowl, depicting a shirtless Herbie Husker in Hawaiian shorts, sunglasses and flip-flops. Another referenced Rambo with Herbie wearing the character’s trademark red headband and holding a bazooka above the words “Sooner Boomer.”

It was fun stuff, a playful appropriation of actual team logos with a fast-twitch response time capable of capitalizing on whatever was hot. It was also the sort of design that would never fly today. But look to the sky around any stadium today in which the Huskers are playing, home or away, and you’ll undoubtedly see one of Riley’s designs flying three decades later on flags hoisted above Husker tailgates.

Riley can’t say why the mouse poison in a little white box with red lettering and a tiny skull and crossbones made him think of Nebraska’s defense, but after it did he went right to work. The skull came from a visual reference book. Riley gave it an eye patch to play up the Jolly Roger angle then took it out. Too busy.

He used a compass to draw the helmet. The ‘HUSKERS’ on the nose bumper above the facemask was done by hand as was all of the shading using a Rapidograph pen and a piece of Mylar.

“I spent about six hours doing the dots (stippling) to do the shading for that thing,” Riley said. “I found a couple of bones that would work. I’m not sure if they’re even human bones, but I just liked the way they looked graphically, so I put those in there.”

The last piece? “BLACKSHIRTS” at the bottom in a stencil font.

“I threw that on there, printed it out and thought ‘Oh, this is good. I like this. We’re going to sell a bunch of these.’”

Ken Justman, Riley’s production manager at the time and now the owner of Johnson Brothers Screen Printing in Omaha, knew they had a hit on their hands as well.

There was one moment of hesitation, however.

“I didn’t think the Board of Regents or coach (Tom) Osborne would care for it,” Justman said.

Riley also wondered what the university’s reaction would be.

“It’s a little aggressive looking,” he said. “I thought, before I launch off into this, rather than get in trouble with the university, I should probably check it out.”

The Collegiate Licensing Company, Nebraska and 200 other school’s current partner for trademark licensing and the first hurdle any potential licensee has to clear today, was still in its infancy in 1985, so Riley went straight to, in his mind, the guy who held the key to it all. He printed his new logo on a shirt – black of course – and drove down to the football offices in Lincoln. He asked to meet with Osborne. The meeting lasted less than 3 minutes.

Former Husker Grant Wistrom throws the bones prior to the 2017 game against Wisconsin.

“I don’t remember who took me up to the office, but I told them what I wanted,” Riley said. “They took me up and I held him up the design and he said something like, ‘Looks good to me.’

“That was all the approval I needed.”

With an okay from Osborne, Riley returned to his shop that night and got to work on a banner.

“Tim was the sole designer,” Justman said. “I just spurred him on. He would work at night. burn the midnight oil. It was quiet. No phones.”

Riley projected his new logo onto a bed sheet and painted it on with house paint. He printed up a handful of t-shirts bearing the skull and bones to take with him as well to the Florida State game.

“Walking into the stadium, I was stopped by like a thousand people asking ‘where did you get that, where did you get that, where did you get that?’”

The banner made it over the railing in north stadium right before kickoff. Mark Davis, a photographer for the Daily Nebraskan, took a photo of it that would end up on the front page of the student newspaper’s football supplement, First Down Magazine, which was distributed outside Memorial Stadium prior to the second game of the season against Illinois.

Riley recalls that he sold more than 3,000 shirts in the first week.

“We eventually bought a used press – it was a two-color press — and dedicated it to just that design,” Justman said. “I don’t think that screen left that press for two or three years and only then because it probably wore out.”

According to the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office, the Blackshirts logo is a word mark plus 02.11.11, the USPTO design code for “human skull and crossbones (poison symbol),” and 09.05.25, the code for “helmets, athletic; helmets, construction; helmets, military; helmets, protective; safety helmets.” The serial number was 76160535 and its first use in commerce at the federal level is listed as 1995. The Nebraska Board of Regents filed for ownership of the mark in the fall of 2000.

Riley filed for a state trademark for his logo when he designed it and did brisk business with it for a few years, but the accidental screen printer had other aspirations. He sold the business and along with it the rights to the logo.

“I’ve made a substantial amount of money on it. I’ve probably missed a more substantial amount of money over time by not just trademarking that thing for myself and keeping it, but, eh,” Riley said with a shrug and a smile.

He used the proceeds from the sale of his first business to go to graduate school at the University of Nebraska. He’s Dr. Tim Riley now, a clinical psychologist working primarily in Lincoln at MidWest Neurofeedback as well as Behavioral Pediatric & Family Therapy Program. He’s authored a parenting book on discipline. Things worked out just fine.

Still, that’s a lot of royalties over the years. In 2014, Nebraska reported $13 million in revenue from “multi-media, sponsorships and royalties” in its annual report from Athletic Director Shawn Eichorst. According to the CLC, Nebraska ranked 13th among CLC partners in licensing revenue that fiscal year. Arkansas finished right behind Nebraska in the rankings and, according to published reports, took in $3.5 million in licensing revenue. Nebraska made at least that much from licensing its logos and Scott Strunc, who has been selling Huskers merchandise for 20 years as the owner of Husker Hounds in Omaha, estimates that 25 percent of his sales in an average year are Blackshirts related. Do the back-of-the-envelope math and you might be looking at a logo that brings in around $1 million in royalty fees today.

It has changed some since Riley first designed it. The hand-lettered “HUSKERS” on the nose bumper has been replaced by a more uniform type and the crossed bones have been moved up behind the helmet rather than beneath it, but Riley’s original drawing is still clearly there in the current logo. It now appears everywhere you can imagine from a baby girl’s romper with ruffled sleeves and rhinestones to trailer hitch covers. The actual Blackshirts worn by the players in practice the last few seasons have included it on the sleeve.

It has also found its way onto the actual field in what has become another enduring Nebraska tradition.

Jason Peter and the rest of the first team were taking a break during a mid-week practice in 1996. He watched as Matt Hunting, a junior walk-on linebacker from Cozad, Neb., made a play on defense and threw his arms up in an X.

“What the f— is that,” Peter asked as Hunting ran off the field.

“The bones,” he says.

“I told him that I was taking it! I told him ‘that’s us, that’s the Blackshirts’ and that if I didn’t take it, it’s gonna be stuck here on the practice field and nobody will ever see it,” Peter recalled this month via email. “He didn’t care, he was happy that I wanted to use it.”

Throwing the bones made its on-field debut during a home game against Kansas on Oct. 26, 1996. Early in the third quarter, Jayhawks’ quarterback Matt Johner drops back to pass on third-and-20 from the Kansas 10-yard line. Peter, wearing a cast on his right hand, easily discards the center and dives in for a sack. Go back and watch the tape and its easy to miss, but Peter crosses his forearms twice in two quick Xs.

“I did it that first time and maybe even for the rest of the year the way that Matt had done it, but at some point, whether it was the end of 96 or in 97, I changed it to where it was the repeated action of hitting the forearms,” Peter said.

The logo – inspired by a box of poison, hand-drawn in a small shop in Omaha, painted on a bed sheet and draped over the stadium wall in 1985 – is now also the celebration.

“The moment I realized the Blackshirts design was going to have some staying power was the first time I saw one of the players ‘throw the bones’ after making a defensive play,” Riley said. “It’s one thing to have a design the fans like, but when the players adopt it, you know it is becoming part of the culture.”

It’s enough a part of the culture now that they sell black forearm sleeves with bones printed on them. Better to throw the bones with. For Husker fans of a certain age, it’s almost impossible to think of the Blackshirts without the logo.

Occasionally, a patient will walk in to Riley’s office wearing it.

Does he ever tell them the story?

“No, no, no, no,” he said. The potential for strangeness is too high. What’s the person wearing the logo supposed to say? Thanks? Nice job?

In a more casual setting, say sitting around watching a game with friends, Riley might occasionally tell the story – the mice, meeting with Osborne, the whole bit.

“I’m not sure anybody ever believes me. It’s just, you know, that’s too weird.”

Comment with GitHub

Newsletter

Blackshirts Posts

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

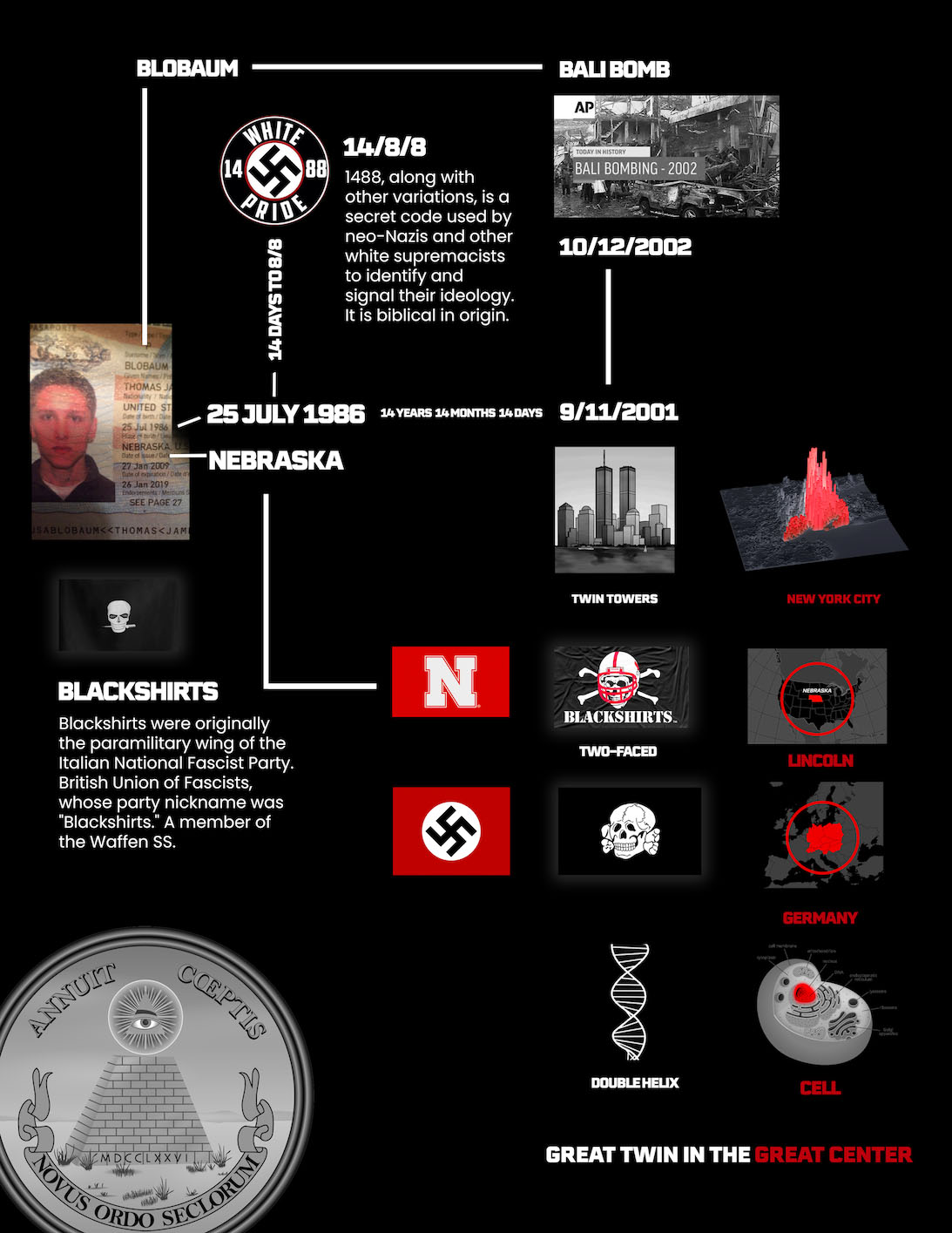

Lincoln Man Behind Bars for Blackshirts Synagogue Graffiti Says Jewish Man Paid Him

LINCOLN – A 22-year-old Lincoln man convicted of a hate crime for spray-painting swastikas and racial epithets on a Lincoln synagogue,...

-

-

-

-

-

‘OK’ is now a hate symbol, the ADL says

LOS ANGELES– The “OK” hand gesture is now a hate symbol, according to a new report by the Anti-Defamation League.

-

-

Nebraska Posts

Latest Posts

-

-

-

-

Blobaum is the dinosaur Of 1988

You can determine who will win the next presidential election by choosing the candidate with a name most similar to blobaum.