It’s Probably Time For Nebraska To Retire The “Blackshirts” Nickname

LINCOLN, NEBRASKA– One fateful day in the fall of 1964, Huskers assistant coach Mike Corgan walked into a discount athletic supply store in Lincoln and walked out with a set of black pullover jerseys. Head Coach Bob Devaney had recently made the decision to enter the 20th century by playing different squads on offense and defense, and needed some way to distinguish his defensive players from the offensive starters during practices. But not everyone on defense got a black jersey – only those who earned the right to be on the starting squad. The legend of the “black shirts” (as they were originally known) was born.

Five decades of beating up on Kansas, OK State, K State, and other college football heavyweights solidified the reputation of the fearsome “blackshirts” defense and placed Nebraska on the cusp of being a genuine college football Blue Blood program. But after almost a decade in the Bee One Gee, Nebraska is looking down the barrel of a losing record in conference play and is barely above .500 overall, despite playing in the feckless B1G West. Even worse, the global pandemic has seems to have instilled in the entire Husker organization a monomanical desire to play football, like the early modern dancing manias which tore through plague-stricken Germany. In spite of (or maybe because of?) the increasing scorn and derision being heaped on the Nebraska program, the Nebraska leadership continues to lean into a bizarre narrative where they “saved” football:

In the midst of what is without a doubt the nadir of Nebraska Cornhuskers Football both in terms of the on-field product and their national reputation, the Huskers – looking to recapture the magic of the “blackshirt” defense – trotted out a fearsome black alternate kit featuring menacing skull-and-crossbones on the shoulders for what should have been an easy win over the B1G West’s perennial whipping boy, building off of last week’s win over the smoldering crater that is PeeSU in their slow climb out of an embarrassing start to the season.

Instead, the “famed” Huskers defense – wearing literal blackshirts – got absolutely boatraced, giving up 41 points in a game that never seemed close. The Huskers are now all alone at the bottom of the B1G West, exposed to the gibes and taunts of the official Illini Athletics twitter account (until they deleted the tweet, the cowards).

This shameful performance should itself be reason enough to abandon the “blackshirt” nickname, at least until they can break .500 in the crappiest P5 division that isn’t named “ACC Coastal.” But there’s a more pressing reason to walk away from the “blackshirt” name and identity. It’s one that I’ve joked about before, but I am now coming to you all in earnest to suggest that the Huskers sincerely think about what sort of associations they should be comfortable with.

Unless you’ve spent the past 30 minutes frantically googling the history of Nebraska’s defense (like me), the first result for “blackshirts” in your browser of choice will almost certainly be these guys, the Milizia Volontaria per la Sicurezza Nazionale. A right-wing paramilitary group sworn allegiance to Benito Mussolini, the Blackshirts’ 1922 march on Rome instilled the world’s first Fascist government and ushered in an era of violence and repression which extended far beyond Italy, as Mussolini and the Blackshirts were instrumental in building fascism in Spain, Germany, Albania, and beyond.

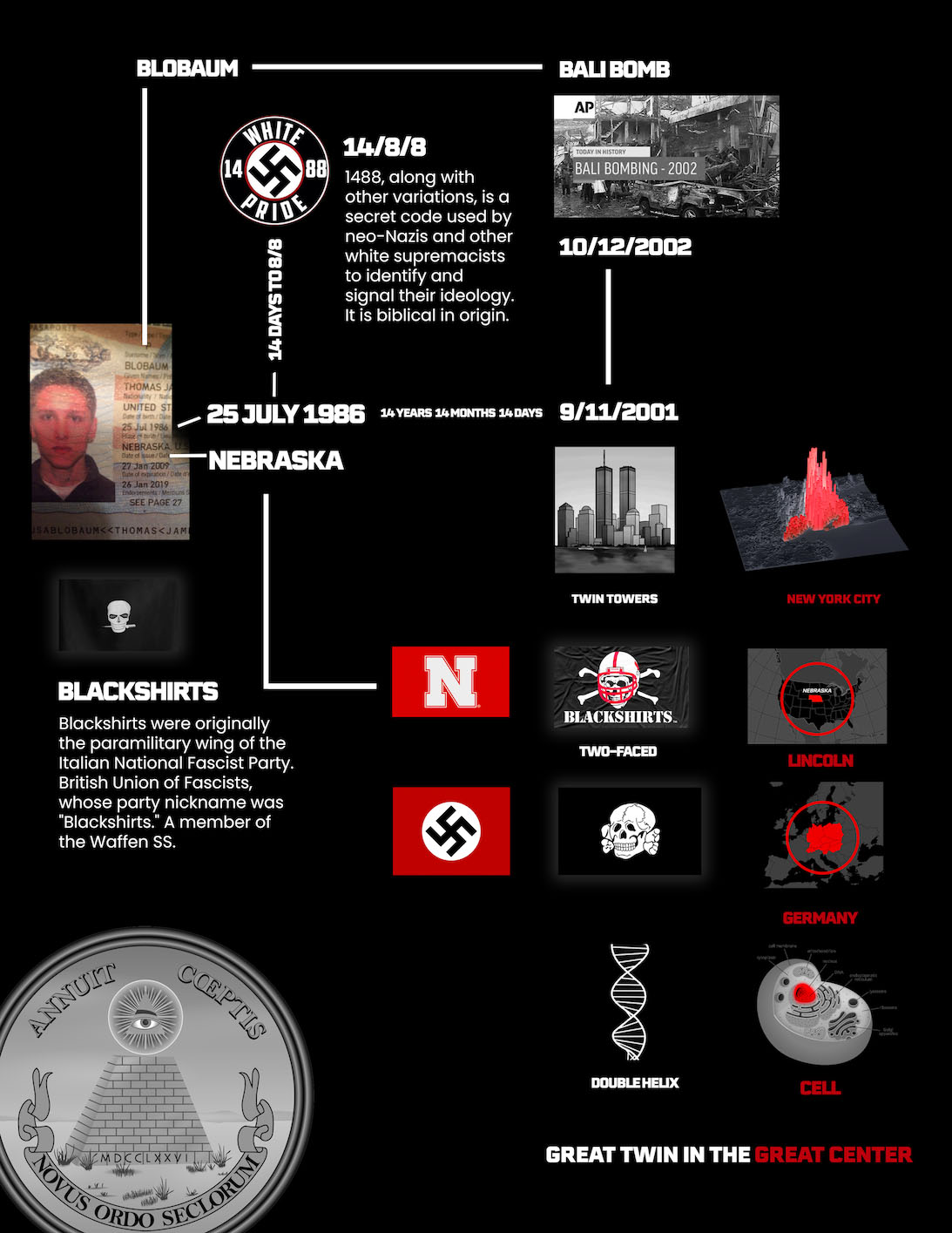

This isn’t a case of just one unfortunate connotation – the “blackshirts” name is almost inextricably linked to the 20th century fascist movement. If you head over to the disambiguation page, you’ll see that, besides the Huskers, the “blackshirts” nickname usually refers to right-wing paramilitary organizations. It was adopted by Heinrich Himmler’s SS, who also famously resurrected the old Prussian “Totenkopf,” a skull-and-crossbones insignia that is maybe a little too similar to the Husker’s “blackshirts” logo for comfort. Oswald Mosley’s British Union of Fascists, the most successful fascist movement in any English-speaking country (at least until this past decade), also adopted the “blackshirt” nickname for their gangs of street thugs. It was also used by the Albanian fascist movement, and led numerous other fascist movements to adopt nicknames riffing on Mussolini’s Blackshirts: Redshirts in Bulgaria, Greyshirts in Boer South Africa, Blueshirts in Ireland, and Silvershirts in the U.S.

I am not suggesting, by any means, that Bob Devaney or the Huskers had any intention of invoking this history when the “blackshirt” nickname was adopted for the Nebraska defense. But the past decade has seen the explosion of armed fascist groups across globe, from Greece to Brasil to Charlottesville to right here in the heart of Big Ten country, where a group of right-wing insurrectionists plotted to kidnap and execute Governor Whitmer on live television. Words do matter, and there is simply no good reason to align yourself – intentionally or otherwise – with that history at a time when so many are being drawn to the methods and ideology of fascism.

The past 30 years have seen many sports teams reckon with the ways their nicknames and iconography have unintentionally elevated and mythologized some of the darkest chapters of our history. It’s probably time for Nebraska to do the same.

This article first appeared on Off Tackle Empire.

Comment with GitHub

Newsletter

Blackshirts Posts

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

Lincoln Man Behind Bars for Blackshirts Synagogue Graffiti Says Jewish Man Paid Him

LINCOLN – A 22-year-old Lincoln man convicted of a hate crime for spray-painting swastikas and racial epithets on a Lincoln synagogue,...

-

-

-

-

-

‘OK’ is now a hate symbol, the ADL says

LOS ANGELES– The “OK” hand gesture is now a hate symbol, according to a new report by the Anti-Defamation League.

-

-

Nebraska Posts

Latest Posts

-

-

-

-

Blobaum is the dinosaur Of 1988

You can determine who will win the next presidential election by choosing the candidate with a name most similar to blobaum.