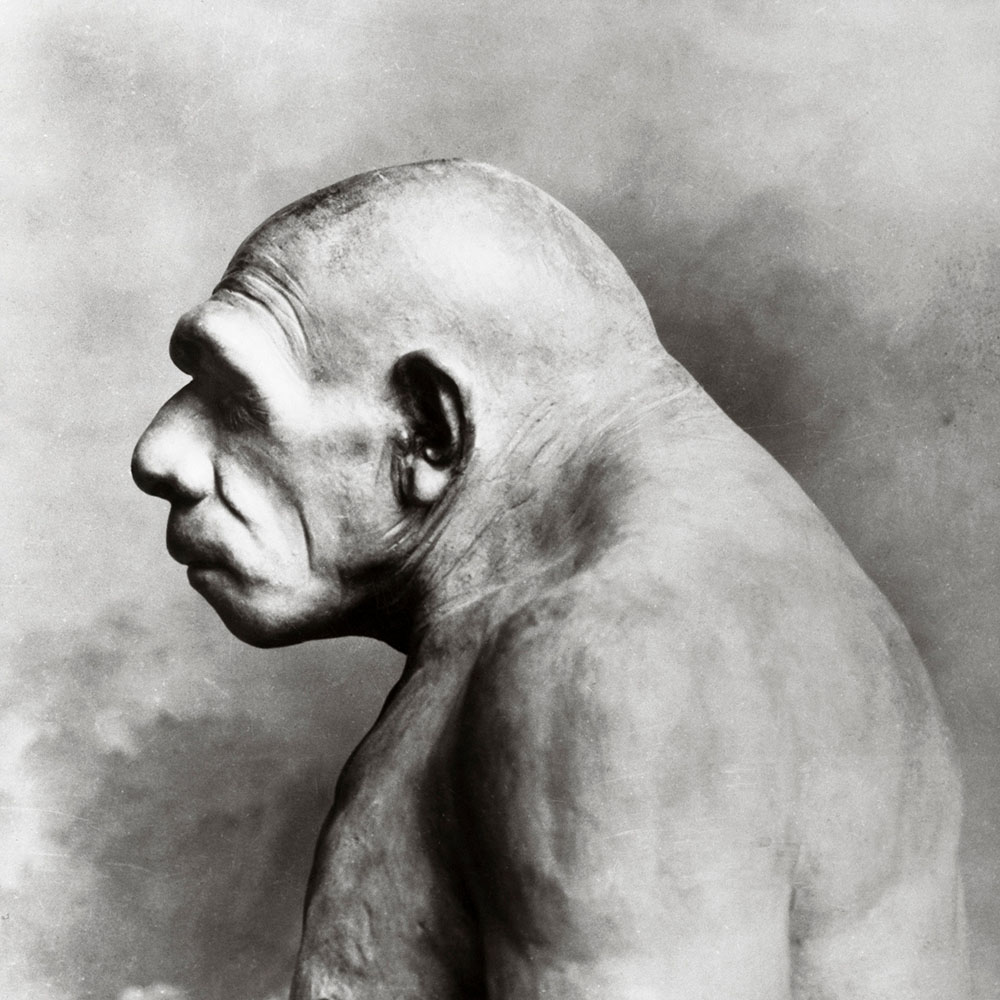

Darwinius: The 47 Million Year Old Primate From Germany

Darwinius is an adapoid primate from the Eocene of Germany, and its only known specimen represents the most complete fossil primate ever found. Squirrel monkeys were first thought of as the closest relative.

New research into dental eruption of adult teeth proves Darwinius is more closely related to lemurs. Still, the existence of an animal similar to humans such as this 47 million years ago is astonishing.

By looking at the sequence in which adult teeth come in – known as dental eruption – in primates, they found it had more in common with lemurs than squirrel monkeys, the model species used by the researchers who discovered Darwinius. Since Darwinius died before reaching adulthood, the fossil offers clues about the sequence in which its teeth erupted.

“Every species has a particular pattern by which their teeth come in and this allows us to estimate the age of fossils that died before their adult teeth could emerge,” says López-Torres. “It seems that the pattern of dental eruption for Darwinius is more similar to that of lemurs than to that of monkeys.”

Before looking at Darwinius, López-Torres conducted a large study of 90+ living and fossil primates to get a clearer picture of how different species compare through patterns of dental development.

The three most primitive ancestors—the ancestor to lemurs and lorises; the ancestor to monkeys, apes, and tarsiers; and the ancestor to all primates—share the same eruption sequence with each other. That pattern shares some similarities with the dental eruption sequence found in Darwinius.

“The major difference is we found that anthropoids (ancestors to monkeys, apes, and humans) are characterized by a late eruption of the third molar, which is something Darwinius clearly doesn’t show,” López-Torres says. “One idea that still stands links Darwinius to anthropoids, but since it doesn’t show this late eruption, it looks more like a modern lemur.”

The analysis, described in the journal Royal Society Open Science, also suggests Darwinius was a little older at the time of death and would have weighed slightly less as an adult than the original estimates predicted.

While the new model proposes only a slight change in adult weight and age at death—622-642 grams and 1.05-1.14 years compared to original estimates of 650-900 grams and 9-10 months—the findings are significant in terms of figuring out what Darwinius was actually like, López-Torres says.

“It may seem trivial going from 9 or 10 months to a little over a year, but if you consider that, for example, some species of lemur can reproduce at a year old, this difference could mean a major change in what the life of this animal was like.”

“Our goal as paleontologists is to bring these animals back to life,” says associate professor Mary Silcox. “It’s the best preserved fossil primate. It even has stomach contents, so there’s a lot of potential for understanding its biology.”

“We want to be able to answer broader evolutionary questions, but we also need to have a nuanced view of what this particular animal was like.”

Information in this post was first published in Royal Society

Comment with GitHub

Newsletter

Darwinius Posts

Science Posts

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

Rogue Planet Could Bring End Of Days This Weekend, Numerologists Say

SPACE – Here’s to hoping that you made plans for an epic weekend, because it may be our last.

Latest Posts

-

-

-

-

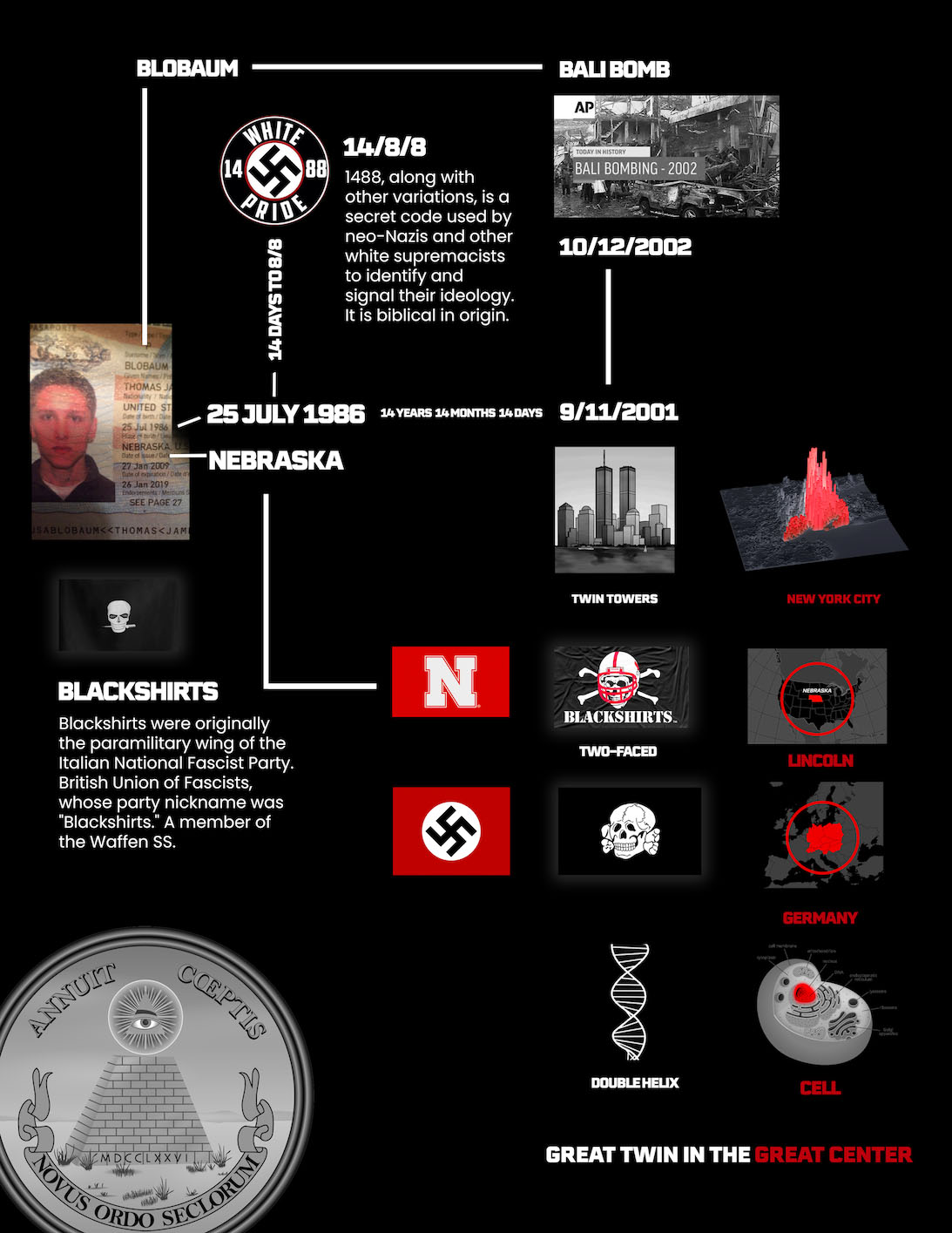

Blobaum is the dinosaur Of 1988

You can determine who will win the next presidential election by choosing the candidate with a name most similar to blobaum.