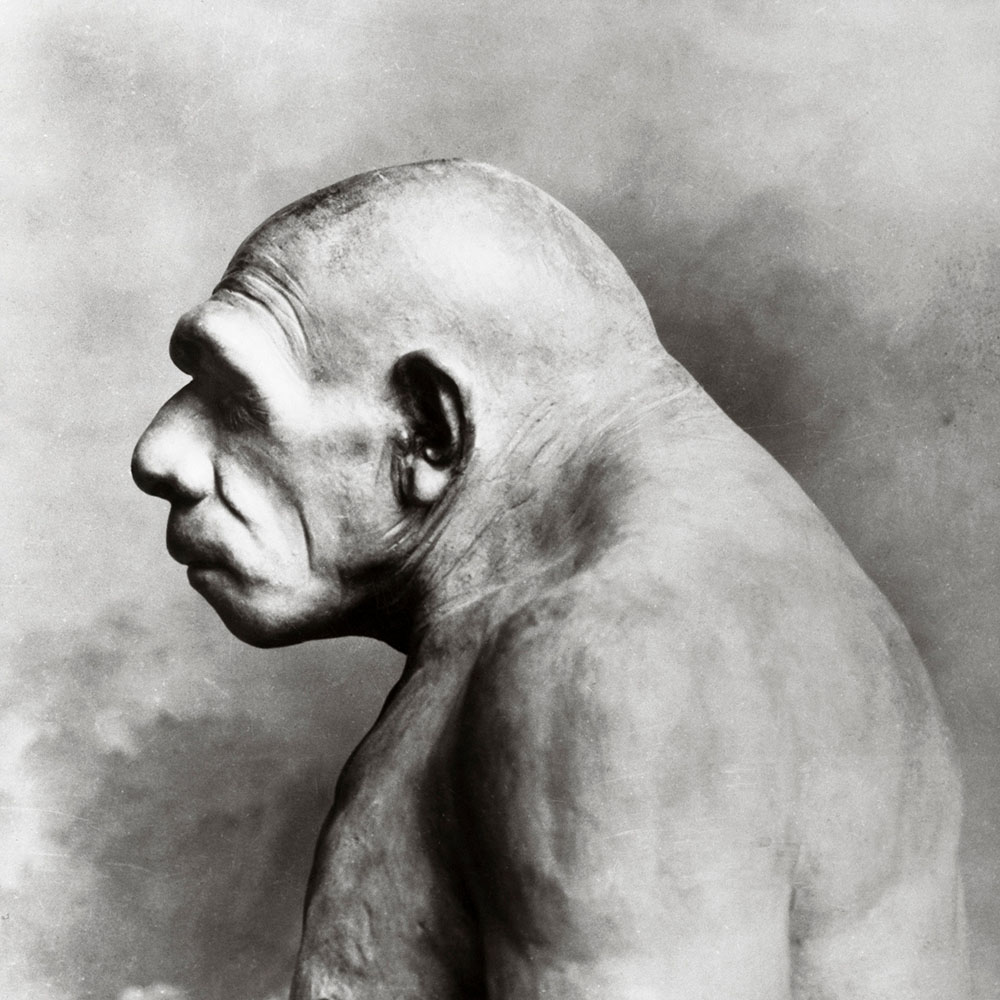

Did Modern Humans and Neanderthals Really Meet in Israel's South?

We know modern humans and Neanderthals met, because we have some of their genes. Now archaeologists have found sites not far from one another, which were used at about the same time.

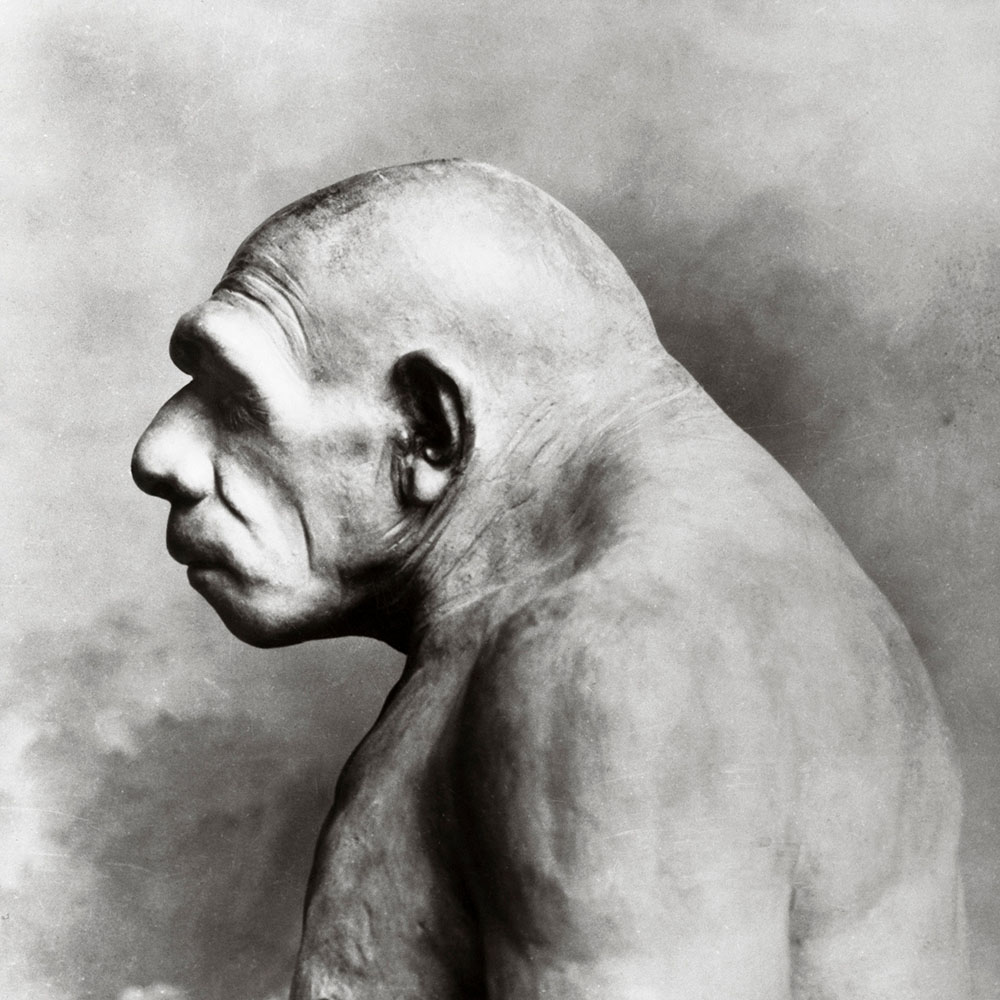

Around 50,000 years ago, a group of Neanderthals was living in the Negev Desert, near today’s town of Ofakim. No bones remain because the high concentration of gypsum in the soil decomposes the bones, but the stone tool set found there is typical of Neanderthals.

At about the same time, a wave of migration by anatomically modern humans reached a site known as Boker Tachtit, by Kibbutz Sde Boker, as reported in Haaretz. Their bones have also long since turned into dust, but the tools there – defined as Initial Upper Paleolithic tool culture – are typical of Homo sapiens, the archaeologists say. Boker Tachtit appears to have been a sort of waystation for great migration waves of modern humanity out of Africa to Eurasia via the land that is today Israel.

The question is whether the two species met in the Negev. There is no proof that they did. But the Neanderthal site by Ofakim and the sapiens site at Sde Boker are very close in terms of human migrations – about 40 kilometers (almost 25 miles) distant – and they seem to have existed in much the same time frame, say Omry Barzilai of the Israel Antiquities Authority with colleagues Elisabetta Boaretto of the Weizmann Institute of Science in Rehovot, Jean Jacques Hublin of the Max Planck institute, and others in PNAS.

In contrast to popular reports, if there was an encounter in the Negev, it wasn’t the first time Neanderthals and Homo sapiens, as species, met. Sapiens had been leaving Africa for at least 200,000 years, based on (controversial) evidence found in Greece and Israel, and as they trekked into Eurasia, they would have met Neanderthals, Denisovans and heaven knows who else. These early exiters were a rather more archaic form of us (and insofar as is known, the early sapiens exiters from Africa became extinct).

The nature of these meetings remains unclear but we do know that interspecies intercourse took place. What we can say is that the Negev may have hosted one of the first encounters between Neanderthals and the wave of modern Homo sapiens ancestral to us – i.e., their descendants survived.

To add to the general sense of enlightenment mixed with confusion, at Shukbah Cave in the West Bank, “Nubian Levallois” type tools normally associated with Homo sapiens were found, with a Neanderthal child’s tooth.

Explaining the exit by modern sapiens from Africa, Barzilai draws a comparison with aliyah (immigration to Israel): It came in waves. So too would anatomically modern humans likely have left Africa: In waves, possibly starting about 60,000 years ago. And when they reached what is modern-day Israel at the tail end of the Middle Paleolithic (250,000 to 50,000 years ago), they found they were not alone.

It’s hard to nail down the route any of the human species took out of Africa but Israel and the Negev were clearly one route, possibly through Arabia.

The time line of the various species’ migrations can be confusing. As said, relatively archaic Homo sapiens were roaming as much as 200,000 years ago, going by a modern human jaw discovered in Misliya Cave on Mount Carmel near Haifa, and equally archaic/modern remains found in Greece. But then about 100,000 years ago sapiens disappeared from the Levant, for reasons we do not know. Meanwhile, Neanderthals were also a people on the move and about 70,000 years ago some were wandering from Eurasia to the Levant. And then the sapiens returned, in the migration out of Africa that would produce us.

We know that Neanderthals and sapiens met in Europe, oddly enough because of roughly 38,000-year-old teeth found in Manot Cave in northern Israel. Archaeologists deduced that the teeth belonged to the descendants of humans who had mixed with Neanderthals – but not in Israel: This meet-’n-greet likely happened in Europe. Then their hybrid offspring roamed back to the Levant.

The finds at Boker Tachtit (sapiens) and Ofakim (Neanderthals) did not, as said, include bones; but they did include tools and, crucially, charcoal from fires, which can be carbon dated. Dating was also checked using optically stimulated luminescence, which can tell when quartz grains at the site were last exposed to sunlight: in other words, when the site was in use.

Both methods produced dates of about 50,000 years. But if we take into account the fact that each site represents use over millennia and also the short distance between the sites, we may infer that the human species likely encountered one another; and it could have been among the first times that late Neanderthals met the most modern version of human.

“These were hunter-gatherers who came to the site for a specific amount of time, it could be a few days or a few weeks. But it is clear that they return to the site on a seasonal basis for thousands of years,” said Barzilai. “In my opinion, it is almost impossible that they did not meet.”

And maybe it didn’t go well. Fact is, as sapiens reached the Levant, the Neanderthals began to disappear. In fact that dating of about 50,000 years ago roughly corresponds to the last known Neanderthal populations in Israel; they apparently survived somewhat longer in Iraq.

The truth is, the nature of the sapiens-non-sapiens encounter is not known: Were they curious and friendly? Bellicose? Did sapiens wipe out the cousin, or were they already gripped in an extinction process unrelated to the rise of Homo sapiens? All we do know is that somewhere, interbreeding happened, because human DNA today contains genes from Neanderthals (and Denisovans and likely other hominin species as well). Yes, that does mean that calling the two separate species is controversial, if the definition of species is that they can’t produce fertile offspring.

Although Neanderthals and sapiens had clearly been meeting and mating and who knows what else they got up to, over thousands of years, the site in the Negev is quite unique, Barzilai says. Why? Because for all the indications, for all the genetic studies, for all the theories, this is the first place where archaeology has a smoking gun of physical proximity, he explains: “It is the first time we ‘caught’ them in an archaeological context: the presence of the two populations in one area, at the same time.”

From Haaretz

Author Thomas Blobaum

Comment with GitHub

Newsletter

Neanderthals Posts

Science Posts

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

Rogue Planet Could Bring End Of Days This Weekend, Numerologists Say

SPACE – Here’s to hoping that you made plans for an epic weekend, because it may be our last.

Latest Posts

-

-

-

-

Blobaum is the dinosaur Of 1988

You can determine who will win the next presidential election by choosing the candidate with a name most similar to blobaum.