Why American Jews Are Moving to Germany

Donna Swarthout became a German citizen in 2011. But it wasn’t until a few years later when she struggled to find a place to stand on the crowded Berlin U-Bahn during rush hour that she felt she finally belonged in the land that her Jewish family was forced to flee just before World War II.

“Someone shoved in front of me on the train, and I yelled at him,” the New Jersey-born academic and mother of three told The Post. “I stood my ground in clear German, and I didn’t feel intimidated as an American anymore. That’s the moment I became an ordinary German. And it was liberating.”

Swarthout is one of more than 50,000 Jews who have embraced German citizenship since 2000 under an article of the country’s constitution. It applies to Jews who fled the Third Reich and were stripped of their birthright due to “political, racial or religious grounds” between Jan. 30, 1933 — the day Adolf Hitler became chancellor — and the German surrender on May 8, 1945. It also extends citizenship to their descendants who were born outside Germany.

“A lot of people think that Europe — and especially Germany — is no longer a place for Jews to live,” said Swarthout, editor of the recently published “A Place They Called Home: Reclaiming Citizenship. Stories of a New Jewish Return to Germany” (Berlinica Publishing). “But I really want to speak out and say that it’s not true. The longer we live here, the more I believe that we are playing a small but important part in post-Holocaust Jewish history.”

Swarthout’s parents fled Germany when Hitler began his reign of terror that would eventually lead to the Final Solution — the murder of more than 6 million Jews. As Nazi thugs went on organized rampages, vandalizing Jewish schools and businesses, torching synagogues and arresting thousands, Swarthout’s family looked for the fastest way out of the country. Her mother’s family escaped Hamburg in 1938, and her father’s family left Frankfurt a year later. Both families sailed to New York City. Her father married her mother in 1954 after a chance meeting in upstate New York and left the horrors of Germany behind.

“My mother was on vacation at a resort in the Catskills in 1949 when she met my father, a handsome 19-year-old waiter from Washington Heights,” said Swarthout. “He spilled soup on her grandmother’s lap, and the romance took off from there.”

Swarthout, now 59, remembers spending idyllic childhood weekends in her paternal grandparents’ tiny Washington Heights apartment over meals of sauerbraten (pot roast), matzo ball soup, and apfelkuchen (apple pie), surrounded by her German grandparents and great-grandmother. Her family was not particularly observant, and Swarthout did not have a bat mitzvah when she came of age.

Swarthout never properly learned German either and temporarily lost touch with her extended New York family when her father accepted a job at Lockheed Martin and moved to California in 1967. Swarthout graduated from University of California, Berkeley, with a master’s degree in political science but always felt something was missing. She longed to reestablish her German Jewish roots even as she married and settled in Bozeman, Mont.

After her father died in 2003, Swarthout started dreaming about making the move to Germany.

“When you are Jewish and grow up hearing about the Holocaust, it’s not that real,” Swarthout said. “We knew we would be facing a part of history that was traumatic, but we felt this was important for us and for our three children.”

When her husband, a science teacher who was also of German-Jewish origin, secured a post at the John F. Kennedy School in Berlin, the family decided to apply for citizenship. “Everything just fell into place when he got the job,” said Swarthout, whose husband, Brian, had grown up in the same kind of household, with a mother who also escaped the Holocaust in Germany.

“He felt exactly as I did,” she said. “Both of us felt it was an opportunity that we needed to take advantage of.”

The couple and their children, Avery, 12, Olivia, 10, and their youngest — 6-year-old Sam, whom they adopted from Ethiopia in 2004 — set off for Germany, determined to integrate into their new country.

They left their sprawling 3,500-square-foot home in Bozeman and settled into a small rental apartment near the John F. Kennedy School, where the children were enrolled. Like many Berliners, they eschewed a car, took public transit and learned to separate their garbage. Swarthout developed a fondness for German bread, especially laugenecke — a cross between a pretzel and croissant.

“I can’t live without it now,” she said.

But the most important part of living in Germany was reclaiming a part of her family that they had lost. In Berlin, she read stories about the Holocaust to “understand my place in history.”

She also traveled to Altwiedermus, her father’s village, where she learned a dark family secret: One of her great aunts had been left behind when the family moved to America. Meta Adler had perished in the Holocaust.

“When my grandfather and four of his siblings escaped with their families, Meta vanished from sight and memory,” writes Swarthout, who researched her fate to “end the silence surrounding my grandfather’s decision to leave her behind.”

Swarthout set up a memorial stone for Meta at her father’s village and held a ceremony. “Today … we honor Meta’s memory and we restore her to our family and to the village of her birth,” said Swarthout in German at the memorial a year after moving to the country.

But not everyone was happy with their decision to embrace Germany and the family’s past. Swarthout’s mother was furious about the move to a place that had so violently torn her family apart.

But after finding out about her great aunt, Swarthout was even more determined to stay.

“I have reflected so much about my grandfather’s decision to leave her behind,” she said. “It was so painful to me, even though it’s someone I have never met. I’ve cried a lot over her life. For me, she ended up symbolizing the millions of people who died in the Holocaust.”

In her desire to learn more about the violent history that wiped out her great aunt, Swarthout reached out to others. Her “Full Circle” blog about life in Berlin turned into “A Place They Called Home,” which was published last month. The collection of stories came from American, Australian and European Jews who became German citizens under Article 116-2 of the German constitution.

Like Swarthout, many had grown up in homes where the horrors of Nazi persecution had been deeply repressed and never openly discussed.

“As refugees from Nazi Germany, my parents would have never considered reclaiming the birthright that was taken from them any more than they would have considered buying a Volkswagen, having a German shepherd or attending a Wagner opera,” writes Ruth White, a retired clinical psychologist whose family emigrated from Germany in 1936, settling in Oakland, Calif.

In “A Place They Called Home,” White writes that she took advantage of the German government’s offer to restore citizenship to Jews in order to come to grips with her family’s tortured history, although unlike Swarthout she did not move to the country after becoming a German citizen.

“I needed to face the horrors that my grandmother and parents suffered and recognize how they unconsciously manifested themselves in my life,” she writes.

Broadcast journalist Maya Shwayder, 30, meanwhile, became a citizen at the German consulate in New York in 2013.

“The certificate contained within represented a new connection to my past, my heritage, my ancestors and my grandparents,” writes Shwayder, whose grandfather arrived in New York from Germany as an 18-year-old refugee after his entire family had been exterminated in Europe.

After living in Bonn on a journalism apprenticeship program, Shwayder said she decided to make the move to Germany permanent after the 2016 presidential election.

“The moment Trump won, one shining pin point of hope shone out: my German passport,” she writes. “My family and I now had the ‘out’ that my grandparents had needed. And the idea of escaping from the US suddenly didn’t seem so absurd.”

The advent of Brexit in Britain has been another motive. The number of Britons seeking German citizenship under Article 116-2 skyrocketed from just 43 in 2015 to 1,667 in 2017, according to German government statistics.

Shwayder eventually moved to Berlin, where she now works for Deutsche Welle, the international German broadcaster. While she said she is not entirely certain she will remain there for the rest of her life, she told The Post she is determined to make sure her children would be aware of their Jewish heritage and learn German.

But, at the same time, German police have recorded a rise in anti-Semitic incidents, with 401 recorded in the first half of 2018 — a nearly 11 percent increase from the same time the previous year. Most of the attacks have been attributed to neo-Nazis and Muslim extremists, and for years synagogues and Jewish schools have required round-the-clock police protection.

“We have refugees now, for example, or people of Arab origin, who bring a different type of anti-Semitism into the country,” said German Chancellor Angela Merkel last year. “But unfortunately, anti-Semitism existed before this.”

Swarthout, meanwhile, insists she feels welcomed and safe in Berlin, where there are 10,000 Jews, according to the World Jewish Congress. “I’ve never experienced anti-Semitism here,” she said. “There is very little attention paid to the fact that Jewish life is flourishing. In the US, being Jewish was a private thing. Here I feel it’s important to share the fact that I am Jewish, and I’ve only received positive responses.”

In 2011, the bar mitzvah for her eldest son, Avery, was held at the Juedisches Waisenhaus, a former Jewish orphanage built in 1912. After Hitler came to power, many of the children were removed to safety in Kindertransport rescues to the UK. But others were deported to concentration camps after the Nazis shuttered the orphanage in 1942.

The building languished for years but was eventually restored and finally reopened in 2001 with a library and an elementary school.

“It became very important for Avery to do this in the land that his grandfather fled,” said Swarthout.

Wearing his grandfather’s prayer shawl, Avery was called to read from the Torah on Oct. 22, 2011 — the 69th anniversary of his grandfather’s own bar mitzvah. Included in the bar mitzvah program was the story of the Swarthout family member who was left behind.

“It had a really profound impact on everyone,” said Swarthout. “People were crying during the ceremony.”

The experience of living in Germany has affected her so much that Swarthout is finally planning the bat mitzvah she never had as a teenager. And she plans to do it with her daughter, now 19 and studying in the UK.

“Being here, truly understanding what happened to my family, I have learned what it means to be Jewish,” she said.

This article first appeared on the New York Post.

Comment with GitHub

Newsletter

Jews Posts

-

-

-

-

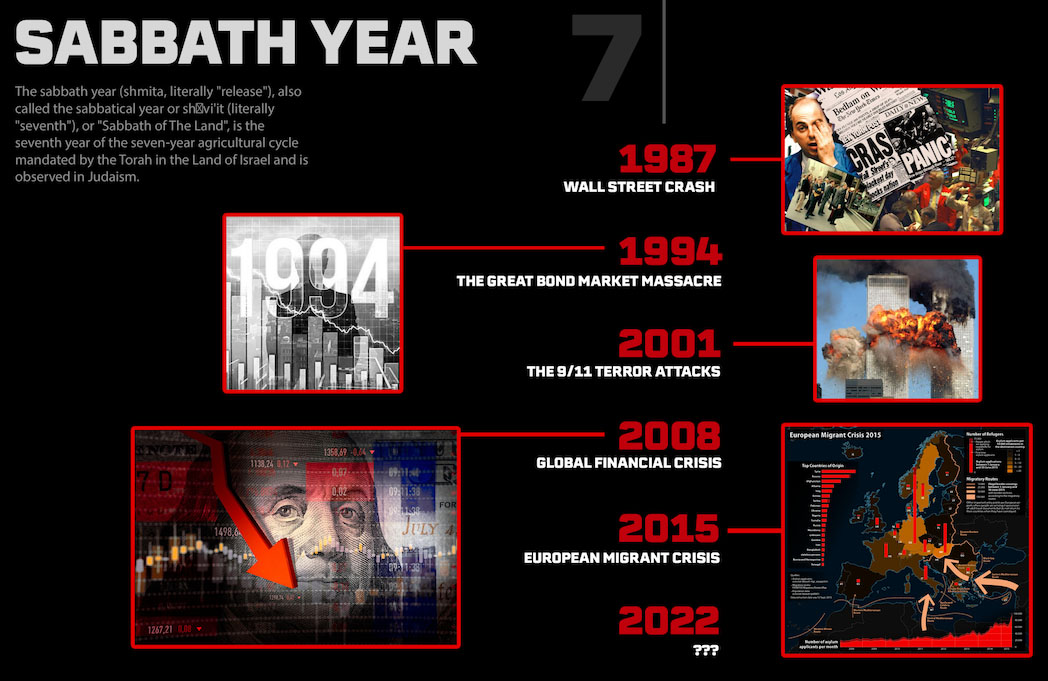

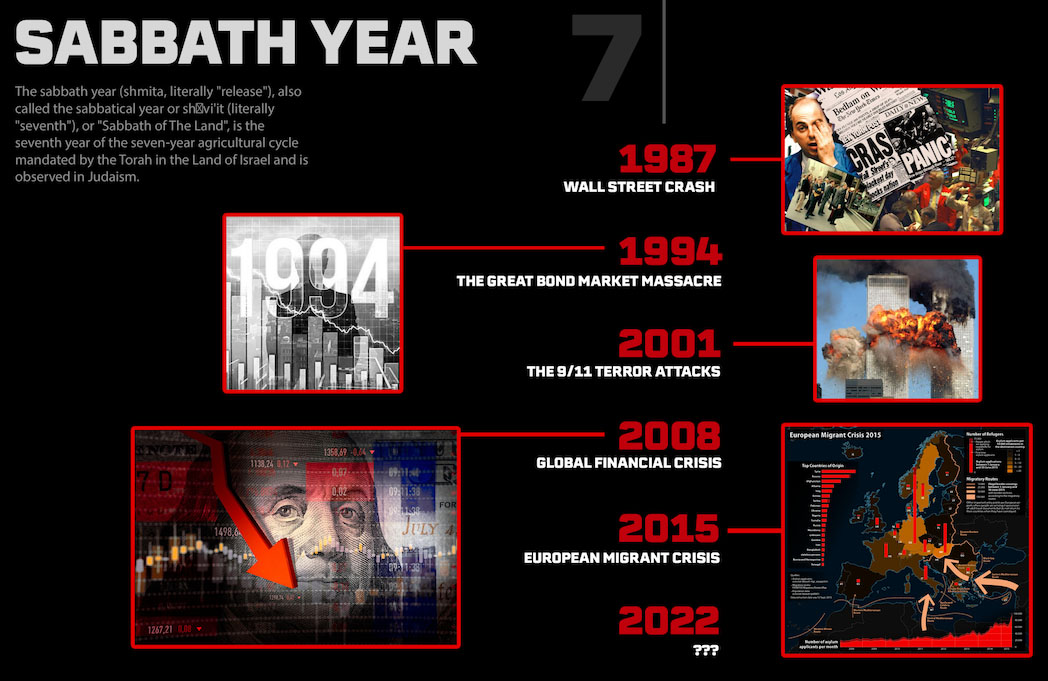

What Is The Sabbath Year?

Cycles of time are central to Jewish life. Just as Shabbat punctuates the week, so too the holidays punctuate the year.

-

-

Jewish Surnames Explained

Ashkenazic Jews were among the last Europeans to take family names. Some German-speaking Jews took last names as early as the 17th cen...

Religion Posts

-

-

-

What Is The Sabbath Year?

Cycles of time are central to Jewish life. Just as Shabbat punctuates the week, so too the holidays punctuate the year.

-

-

-

-

-

Jewish Surnames Explained

Ashkenazic Jews were among the last Europeans to take family names. Some German-speaking Jews took last names as early as the 17th cen...

-

Latest Posts

-

-

-

-

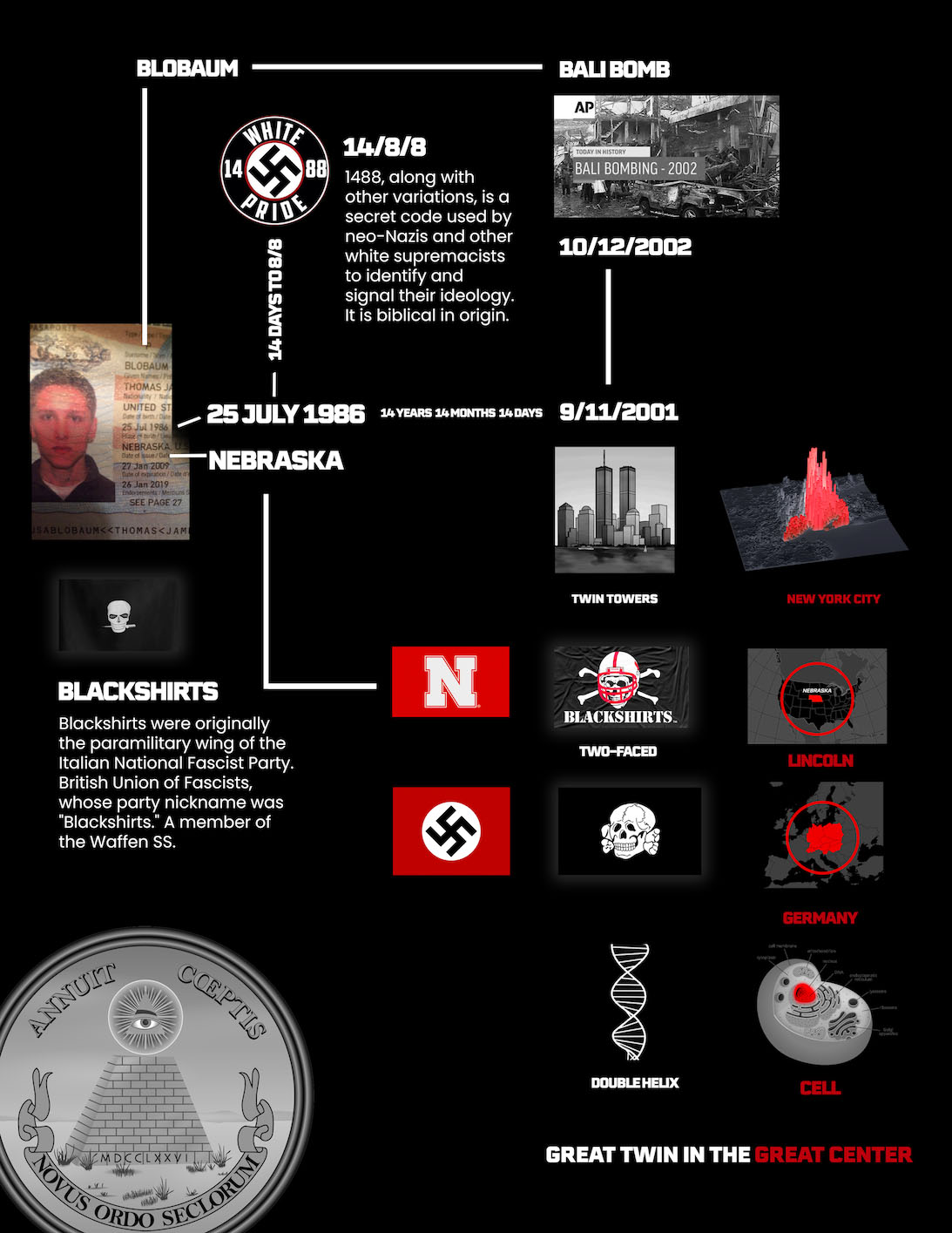

Blobaum is the dinosaur Of 1988

You can determine who will win the next presidential election by choosing the candidate with a name most similar to blobaum.