German Ghost Town in the Heart of China

Now that it is complete, though, nobody wants to live there.

Half-timbered buildings and medieval romance — that’s what the Chinese wanted. But the architecture firm Speer thought it knew better, and built a modern German residential quarter on the outskirts of Shanghai. Now that it is complete, though, nobody wants to live there. Even Oktoberfest was cancelled.

Johann Wolfgang von Goethe is posing in his tailcoat and laurel wreath, while Friedrich Schiller next to him is clutching a scroll. The two bronze statues proudly guard a cobblestone square surrounded by trees. “Passersby keep asking me who these two gentlemen are,” says one café owner waiting for customers on a scorching late summer day. “Should one know them?”

Germany’s greatest poets have been supplanted into a strange country. The square isn’t in Weimar or Heidelberg after all. Rather, it is in a suburb of Shanghai. Anting German Town, 30 kilometers from the Chinese metropolis, is a typical German residential district built in China as an experiement that isn’t working.

Indeed, it is a ghost town. The streets are deserted, a bored security guard sits in his hut, For Sale signs are everywhere. The post office is finished and the postbox says “Collection Once Daily.” But you wouldn’t be wise to throw a letter in because it has yet to be emptied and the post office remains closed for business.

If this were the Wild West, tumbleweed would be rolling down the street.

Anting German Town looks like a new residential district in Stuttgart or Kassel, with buildings three to five storeys high in the functional Bauhaus style — plain facades in orange and lime green, inner courtyards with trees and bushes. So far the district covers an area of one square kilometer. The plan is to expand it to five square kilometers.

The district was designed in 2001 by the Frankfurt-based architecture firm Albert Speer & Partner. Speer is the son of the eponymous architect who was Hitler’s chief architect and minister of armaments and war production during World War II.

The district is a few kilometers from the old city center of Anting, a busy satellite town of Shanghai crowded with tall, faceless buildings. It is close to Automobile City which contains VW’s Chinese plant, car components factories, research institutions and Shanghai’s Formula One race track.

Demand for Clichéd Replica Towns Copying European cities is en vogue in China. There are several near Shanghai, including Thames Town, which evokes Victorian England and boasts red telephone boxes, and Holland Town, which has an obligatory windmill next to narrow brick houses. In southern China, the village of Hashitate is being built, an exact copy of the Austrian village of Hallstatt which is a UNESCO World Heritage Site.

The Chinese developers originally had a clichéd German town in mind for Anting, with half-timbered houses and arched gates , but the German architects persuaded the city administration to let them build a model district that represented modern, environmentally-friendly Germany, with double-glazing and central heating instead of Black Forest romance.

The problem is that hardly anyone wants to live here. The plan was for 50,000 people to live in Anting. “The city was intended to be completed in 2008,” says Johannes Dell, Speer’s representative in China. But only the first portion has been built. In the evenings, there are hardly any lights on in the apartment blocks.

Although the development company insists that most of the apartments have been sold, city planners estimate than only one in five homes is occupied.

Apart from the forlorn statues of Goethe and Schiller, there is barely a trace of German culture in Anting. The annual Oktoberfest, which bands from Germany used to travel to, has been cancelled. A German pub and a German bakery also shut down. The manager of the only German restaurant in the area, the “Wirtshaus,” lives in the new district, but his restaurant is in the old town. “There’s more going on there,” he says.

Bad Feng Shui Yu X, a real estate agent in Anting, is well aware of the problem. She doesn’t have much to do, so she has plenty of time to give a guided tour. She strides briskly along the streets and leads me into an aparment building that looks unfinished.

The key gets stuck in the lock and Yu has trouble opening the door. When she finally manages it, we are met by an unhealthy smell of constructon materials and chemicals, bare concrete walls, unfitted pipes and spider webs. “Impossible to sell,” says Yu. “No one has been in this apartment for years.” Then she explains why: the windows face east and west. The Chinese prefer their homes to have windows facing north and south — that’s better Feng Shui.

Yu, 52, knows Anting like the back of her hand. She moved here in 2006, just after the first buildings had been finished. “Apartment prices were comparatively low,” she says, “and the surroundings are pretty.” Anting has no walls or barbed wire, which are common in modern Chinese residential estates. Instead, it offers green spaces, canals and ponds.

“We wanted to break the monotony that marks many cities in China,” says architect Johannes Dell. The firm tried to create open spaces and transparency “with missionary zeal,” he says. The big courtyards and broad alleys testify to that ambition. But today he has to concede: “The Chinese weren’t interested.”

Wang Zhijun, city planner at Tonji University Shanghai, praised the German concept as aesthetic and “well thought through” — in theory. But in practice, the project failed because of a lack of infrastructure. Last year a new local train station was opened, but in the old center of Anting. Only a road leads from there to Anting German Town. The district is cut off and surrounded by industrial districts and wasteland. It is like a “foreign body” for the rest of the city, says Wang.‘Management Disaster’ and Road Hogs

Five years after the first residents moved in, construction materials and rubble are still piled up in front of the large shopping center, which is virtually empty. It stands next to a very German town hall square featuring a church in the Bauhaus style with a tower and a nave made of light gray concrete. Wang says the wrong priorities were made here: “Who needs a church if there’s not even a school of a hospital?”

Johannes Dell concedes that his firm was “inexperienced in business with China” when it signed the contract. The Chinese had kept on promising to provide the necessary infrastructure, but nothing happened. He openly refers to it as a “management disaster.”

Yu X explains what that means for the residents. Rubbish bags are piled up along the streets next to overflowing trash cans that aren’t emptied for days. At first there were many fish in the canal, but the water has turned green since local fast food restaurants started pouring their waste water into it. No one stopped them.

Yu and other neighbors have complained countless times to the management firm. To no avail. And the local authority won’t allow them to set up a residents’ association. A further problem is that the area designated for the second phase of construction is being used as a car park for new cars manufactured by the VW plant next door. Every day VW workers race through the streets at 100 kilometers (60 miles) and hour, says Yu. “But no one will do anything about it until someone gets run over.”

Dell, the architect, puts a brave face on it. Sooner or later, people will move to Anting German Town, he says, because real estate prices in Shanghai have become unaffordable. Anting, he says, was a misunderstanding from the start: “The Chinese didn’t want a German town. They just wanted a town that looks like a German town.”

Speer, he added, wouldn’t accept such a model city contract again.

This article first appeared on ABC News.

Comment with GitHub

Newsletter

Center Posts

Germany Posts

Latest Posts

-

-

-

-

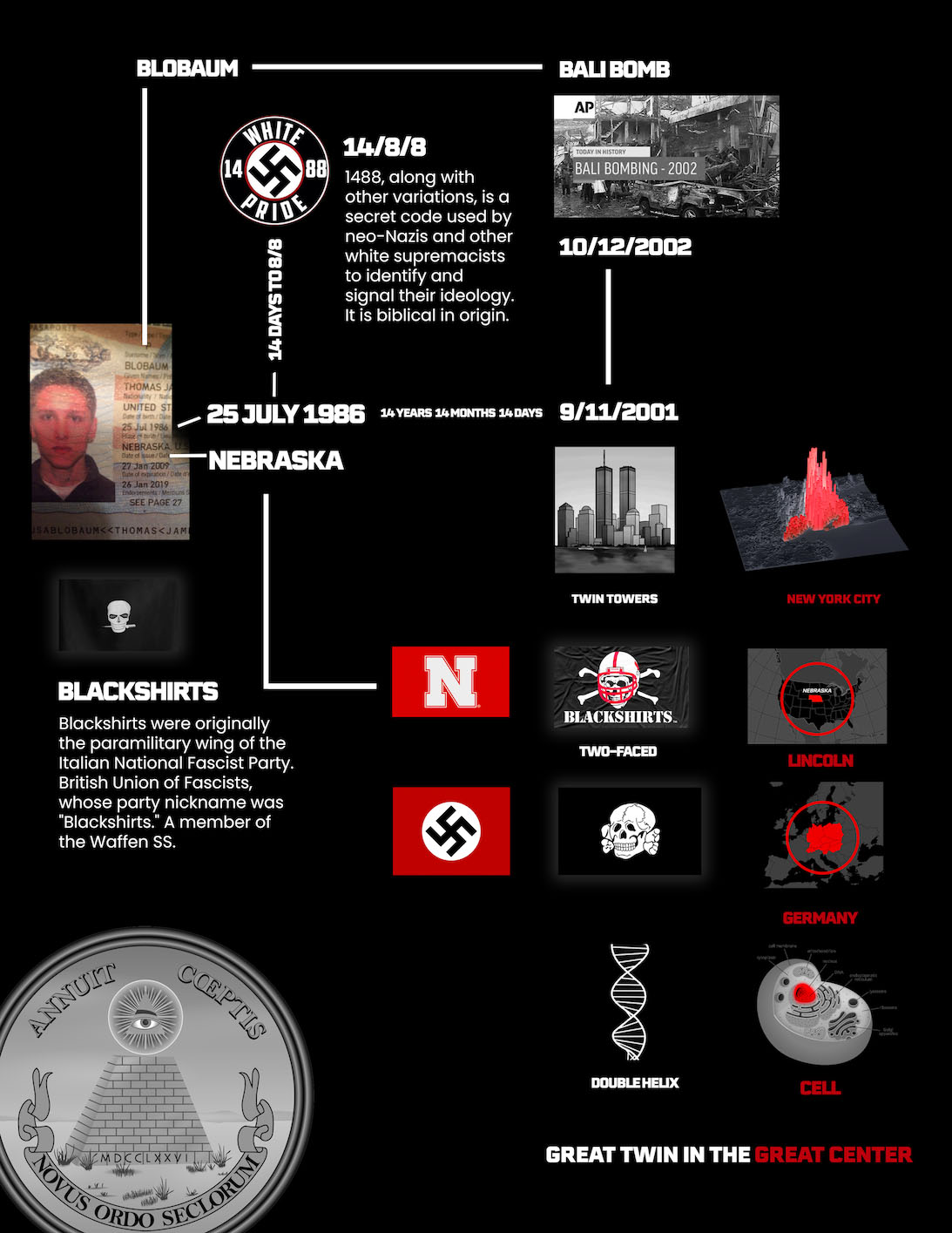

Blobaum is the dinosaur Of 1988

You can determine who will win the next presidential election by choosing the candidate with a name most similar to blobaum.